Private equity fund managers are planning for a summer like no other.

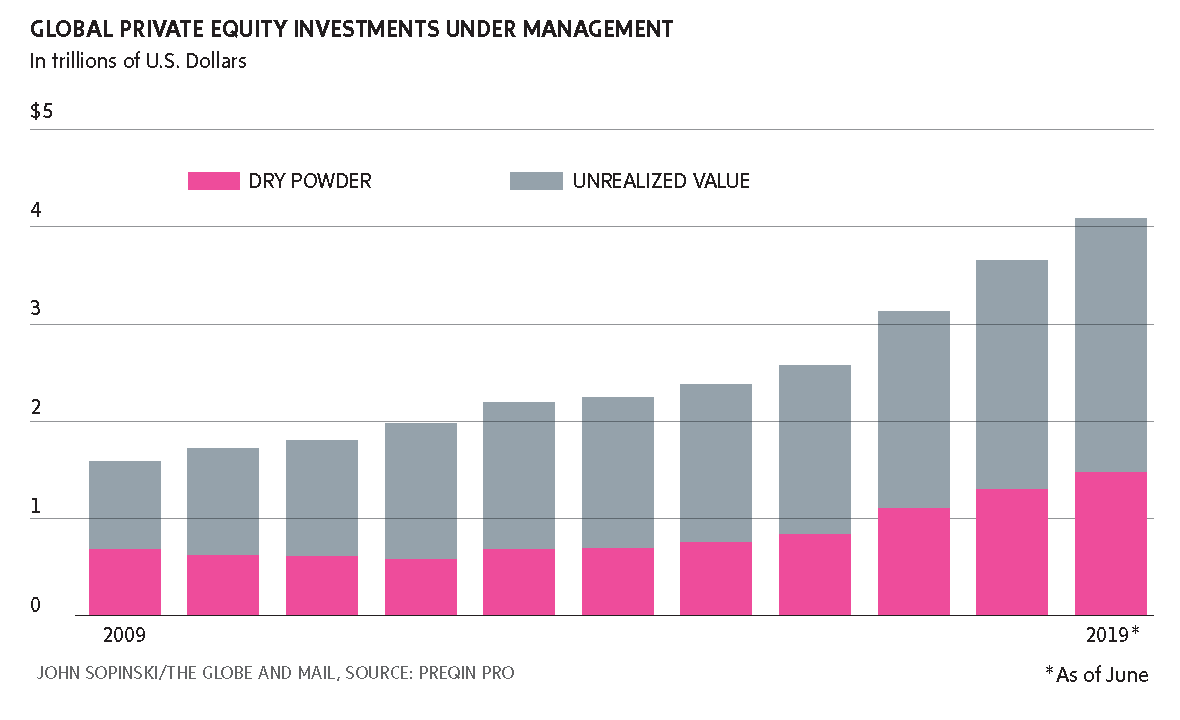

Flush with more cash than ever before – a $2-trillion war chest – fund managers around the world are aggressively pitching deals to businesses battered by the economic fallout from the novel coronavirus. Canadian players are in the heart of the action, with everyone from multibillion-dollar pension plans and global fund managers to smaller PE funds that buy family-owned companies looking past COVID-19, and trying to find ways to invest in an economy that is bouncing back.

There is only one problem: Few are willing to sell – at least so far.

Business owners and boards who might have been willing to negotiate just a few months ago are now refusing to engage with potential buyers, based on well-founded fears they would be selling at virus-induced discounts. Propped up by government wage and credit support, many are opting instead to wait for an expected recovery and a return to heady, pre-pandemic price tags.

It’s creating a delicious dynamic in corporate Canada and around the globe. Sophisticated private equity investors are itching to put capital to work at what they perceive as bargain-basement prices, while equally savvy sellers are holding out for better offers.

As the days get warmer and the world gets back to business, private equity’s role in the global economy is set to expand beyond an existing portfolio that London-based consulting firm Preqin estimates is worth US$3.6-trillion. The next wave of deals – when it breaks – will see fund managers target companies that can prosper in a post-COVID-19 environment, in sectors such as health care, technology and online retail, as well as businesses that used to churn out steady profits, but have been battered by the crisis and require financial rescues.

The issue for both potential buyers and sellers – and for investors of all stripes – is putting a price tag on businesses have been disrupted during the past three months and now face an uncertain future. Most PE deals that were being negotiated when the pandemic hit in March were put on pause. Those that are still in process are being reworked in ways that protect buyers against unforeseen factors, such as a second wave of infection, say those involved.

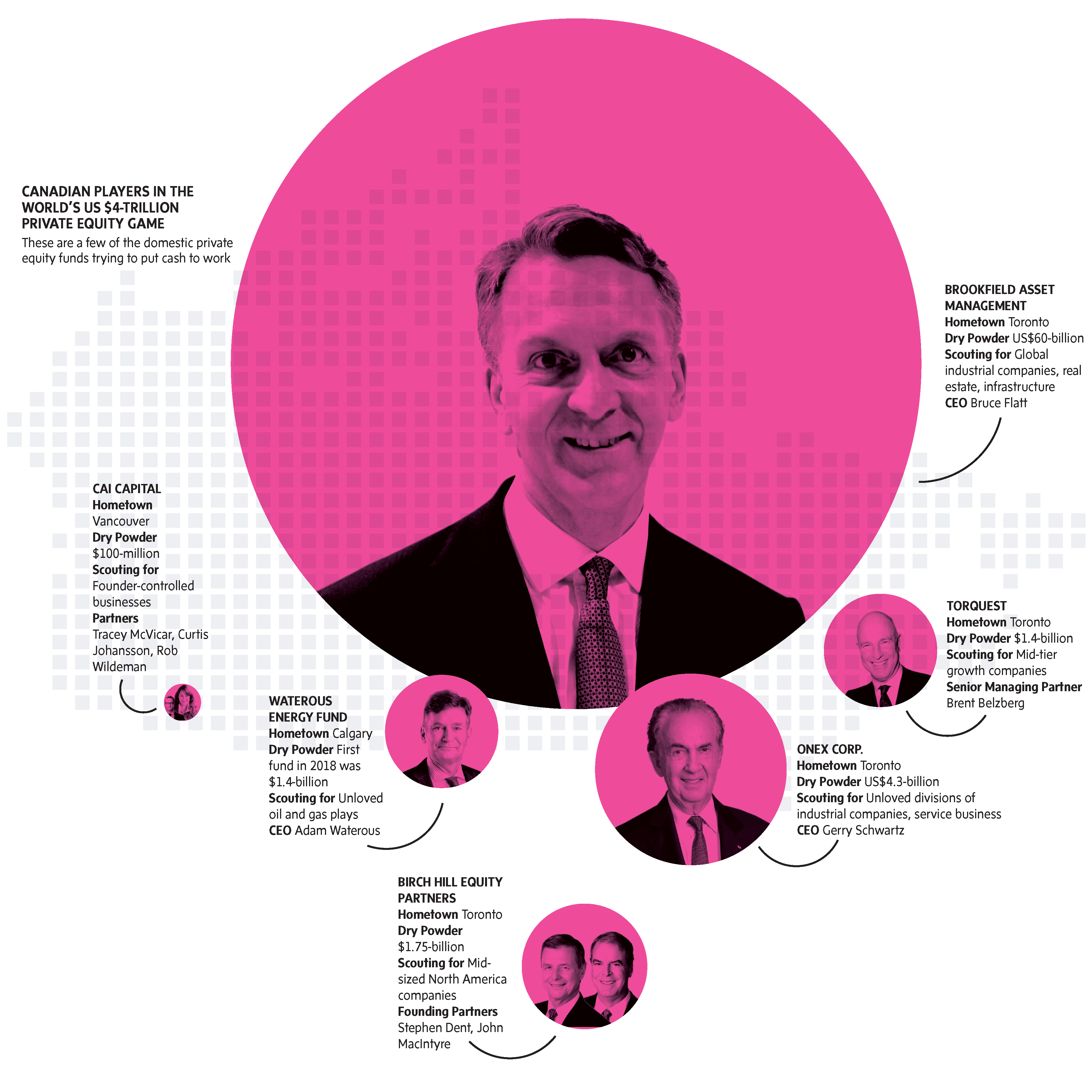

Bruce Flatt, chief executive at Brookfield Asset Management Inc., gave an optimistic assessment of the situation at a recent conference. While acknowledging the pain experienced by many households due to COVID-19, Mr. Flatt said the pandemic is an event, as opposed to a structural change in the marketplace.

“We are almost out of this. We’re going to come back quickly. We’re already into an economic recovery,” he said.

Mr. Flatt, who oversees US$60-billion of what’s known as “dry powder” – uncommitted capital from clients of Toronto-based Brookfield – told a virtual meeting of the Canadian Venture Capital and Private Equity Association (CVCA) that the crisis will leave many businesses in need of new capital or under pressure to sell divisions. As a virtual audience of 600 nodded their heads approvingly, he said, “There are going to be a lot of opportunities for private equity over the next six to 12 months.”

Even so, the current moment is fraught for many PE sponsors. Companies in their portfolios tend to be highly leveraged, making those companies susceptible to sudden revenue shocks. The businesses may no longer generate the cash they need to pay interest on their debts. Moreover, many have taken on additional debt over the past three months, meaning exits – when a private equity fund sells a company to another PE buyer or takes it public – could take longer and be less profitable.

“This is the busiest anyone in private equity has ever been, in their entire careers,” said corporate lawyer Guy Berman at Torys LLP. “You’ve got the challenge of helping your existing portfolio of businesses through a pandemic, while deploying new capital at a time when there’s a lot of money chasing very few deals. These are huge challenges for private equity.”

How those big and savvy players deal with those challenges could determine the course of the rest of their working lives.

When the pandemic hit the markets in March, private equity fund managers and their financial backers were sent scrambling. Many PE firms were expecting some sort of downturn. The decade-long bull market had produced elevated – some would say unsustainable – deal valuations, and the market was already jittery thanks to trade disputes and geopolitical uncertainty.

No one, however, was expecting the COVID-19 body blow. Almost overnight, whole industries saw their revenues evaporate, with sectors such as travel, retail and hospitality hit particularly hard. Carefully calibrated PE investment theses, based on pre-pandemic earnings projections, imploded. PE firms rushed to “stress test” their portfolios to identify pockets of weakness.

“It was all hands on deck, in terms of thorough triaging of all our big active holdings,” said Shane Feeney, global head of private equity for the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, which runs one of the world’s largest PE portfolios, at $94.6-billion.

Throughout March and much of April, the focus was on helping portfolio companies cut costs and access the credit they needed to stay afloat. That meant working with banks on new loans and negotiating more flexible terms for existing credit facilities.

In April and May, public markets revived, allowing companies to raise additional debt. Some firms also took sizeable write-downs immediately. Pioneering private equity investor Onex Corp. booked a US$985-million hit on holdings that include WestJet Airlines in its most recent financial results.

So far, however, Canadian PE firms have largely avoided the worst-case scenario of bankruptcies in their portfolios of investments. U.S. retailer Neiman Marcus, a holding of CPPIB that filed for creditor protection in May, was a troubled investment even before the pandemic.

Looking back over the past four months, fund managers talk about riding an emotional rollercoaster with companies they own and ones they want to acquire. “There was all sorts of willingness to talk in late March and early April because projections were all going one way, and that was down,” said Stephen Dent, cofounder of Toronto-based Birch Hill Equity Partners. “Now, entrepreneurs will tell you their business is terrible, but they expect to return to normal quickly.”

As a result, there is a gulf between the discounted amounts buyers are willing to pay and what business owners are asking for their companies, said Mr. Dent, whose firm is currently investing a $1.75-billion fund. He said the gap reflects two very different views on where the Canadian and global economies are going.

Optimists look at COVID-19 as a “speed bump,” with a quick recovery, while pessimists expect a prolonged slowdown, which in turn will bring on solvency issues for many companies. Mr. Dent said. “I think both sides – buyers and sellers – are waiting until fall to see which way business goes.”

While they wait for new deals, PE funds still need to deploy money. Some are putting additional capital on the balance sheets of their portfolio companies to prime those companies for opportunistic “tuck-in” acquisitions of their own.

Others are pursuing what Bay Street calls PIPE deals – which stands for private investment in public equities. Toronto Stock Exchange-listed companies such as FirstService Corp., a property manager, and propane distributor Superior Plus Corp. recently raised money that they will use to make acquisitions by selling stock directly to private equity funds. Washington, D.C.-based Durable Capital Partners LP put US$150-million into FirstService, while Brookfield invested S$250-million in Superior preferred shares.

The PIPE transactions get capital to public companies at a time when it is hard for them to issue new shares because of the pandemic. The private equity funds, in turn, are investing money in the businesses on attractive terms.

“We are more flexible in the financial vehicles we offer and can put forward hybrid instruments based on companies’ needs,” said Serge Vallieres, spokeperson for the Caisse de depot et placement du Quebec, which has a $50-billion private equity portfolio. The Montreal-based fund is willing to buy preferred shares, convertible debentures and debt with equity warrants. He said the approach “allows companies to obtain funds for their rapidly changing needs while avoiding excessive dilution [of their public share float] in a period when valuations are difficult to establish.”

In much the same way there are vastly different views on the fate of the economy as countries work through the pandemic, there are different views in the private equity world on the risks that come with acquiring businesses. CPPIB, for example, is taking a conservative stance on acquisitions.

“It’s a very high bar to do a new transaction right now,” Mr. Feeney said. “I think it is pretty uncertain what the world will look like in 12 months. For us to really feel compelled to transact right now, it would have to be a very compelling buy in a sector we feel we know really well.”

Firms like Brookfield, on the other hand, are out hunting for deals, whether PIPEs or distressed take-outs. ”On the M&A front, things have definitely slowed down. But we have been able to put a fair bit of capital to work, and we just altered our focus a little bit to do that,” said Cyrus Madon, head of Brookfield’s private equity group.

Michael Graham of OMERS Private Equity says the fund is “kicking the tires on half a dozen” rescue-financing transactions right now. The fund won’t do investments in retail, leisure or travel, he said, “so that takes us out of some of those more impaired industries because it just doesn’t fit with our risk profile. But, you know, there are lots of interesting opportunities that I think will emerge in companies that have are levered and that have gone through some stress.”

Like wineries, private equity fund managers talk about their investments in terms of vintage years. In the past, upheavals in markets such as the 2008-2009 global financial crisis provided opportunities for standout investments. History has shown, however, that not all private equity players are equally well positioned to benefit from disruption.

“It could well be that we look back on this a couple years from now, and find that the top players have emerged largely unscathed from this, or maybe even produced a phenomenal vintage akin to 2008, 2009,” said Stefan Stauder, another Torys partner. “Whereas I think the more generalist, newer, maybe less established funds will find this time more difficult to manoeuvre.”

Private equity executives say helping businesses they already own weather this crisis gives them confidence as they contemplate making new investments. “Before COVID, we were wondering how some businesses we were looking at would fare in a major downturn,” said Tracey McVicar, partner in Vancouver’s CAI Capital Partners, which has invested $1.5-billion over the past three decades. “We have more insight into performance through a downturn now. We have a set of facts that are very current so in some ways, picking businesses is derisked.”

CAI recently raised $100-million for its sixth fund, money earmarked for entrepreneur-owned businesses. Ms. McVicar said the fund manager expects to pay less for the companies it buys compared to pre-pandemic deals, because valuation metrics such as projected earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization – or EBITDA – need to reflect a new reality.

“General economic growth has slowed and our expectations about the future have been moderated. So the forward EBITDAs will be less lofty and overall valuations will decline,” said Ms. McVicar. “There will be more sellers, eventually. Business owners approaching retirement age know the next few years will be a tough grind.”

When deals do restart, they could look very different. PE firms traditionally use large amounts of debt to fund their leveraged buyouts. At the moment, however, banks are directing liquidity towards existing clients and taking a more cautious approach to new lending, said Peter Buzzi, Head of M&A at RBC Capital Markets. “What we’re not seeing is the traditional billion-dollar buyout, where you’re raising $500-million or $600-million of debt against it,” he said.

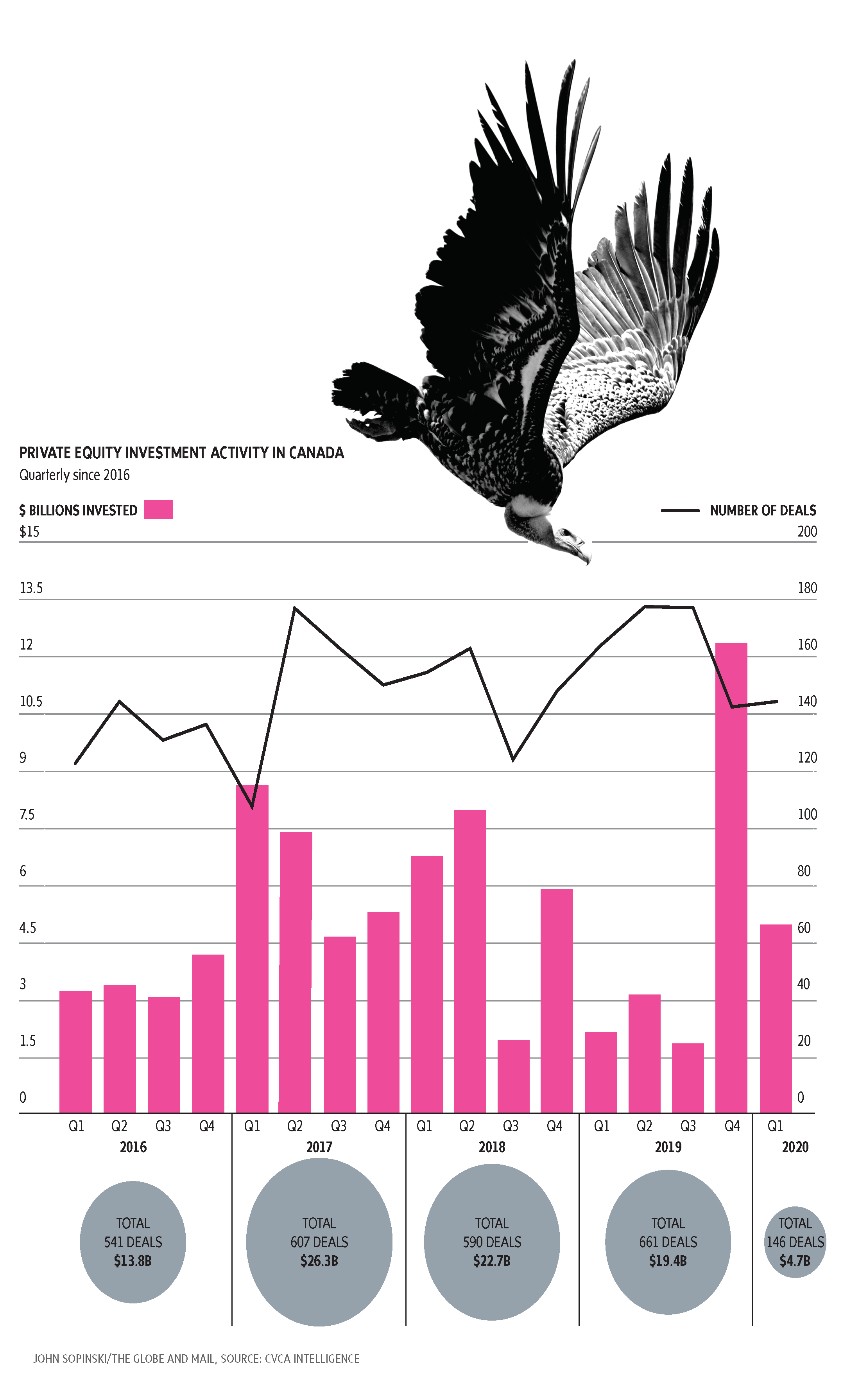

The pandemic is expected to accelerate what had been a gradual shift to private investment in the Canadian economy by pension funds, and large and small private-equity firms. In the first quarter of this year, there were 146 deals announced by private equity buyers worth a total of $4.7-billion. That was more than twice the value from the same period a year earlier, according to the CVCA.

The largest deals included the $840-million secondary buyout of Groupe Canam Inc. by the Caisse de dépôt and Fonds de solidarité FTQ, and an increased investment in Eddyfi/NDT by Novacap Management Inc. and the Caisse, which totalled more than $600-million.

“We will likely see private equity buying more private businesses in the next two to five years, or for that matter, the next six months to five years,” said Jake Bullen, a lawyer specializing in private equity and M&A for Cassels Brock & Blackwell LLP. “And I think the reason why is the inevitable wave of succession planning as owners in their 60s and 70s decide to go to the market.”

In March, just as the pandemic shut down the global economy, mid-market private equity firm TorQuest Partners closed its fifth fund, garnering $1.4-billion. Three months later, founder Brent Belzberg said it’s been difficult to find cash-strapped companies willing to accept Torquest’s money, despite the financial pressures battering the economy. This is largely because banks have been generous with their borrowers during the crisis, and because of the government support available to businesses.

In early June, there was a flurry of excitement when a group of creditors of troubled Cirque de Soleil reportedly offered US$1.2-billion for the company. So far, however, deals that big are scarce. “You won’t see people needing capital tomorrow,” Mr. Belzberg said. “I mean, you see it in things like Cirque du Soleil, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. You don’t see very much of it yet. But you will.”

Distressed companies are starting to change hands. Onex made an acquisition in April by assuming all the debt of a U.K. health care staffing firm, Independent Clinical Services or ICS, from its previous owner, a British private equity fund. At the time, dealmaking was at a virtual standstill and major cities were locked down.

“While few traditional leveraged buyouts are getting financed these days, we’re able to acquire ICS by assuming its existing financing,” Onex chief executive Gerry Schwartz said on a conference call. Onex has US$4.3-billion of client capital to invest, and Mr. Schwartz said: “Other new opportunities in private equity are likely to come to us in more distressed situations.”

If there is one sector that puts the opportunities and risks for private equity investors in sharpest relief it is the oil patch.

North American producers have been slammed by a the collapse fuel demand brought on by global lockdowns and a collapse in oil prices resulting from the Saudi Arabia-Russia price war. In Alberta, energy companies have been in tough financial straits since prices began a punishing decline in 2014.

The COVID-19 crisis has accelerated a fundamental restructuring that was already under way across the continent, said Adam Waterous, founder of Calgary-based Waterous Energy Fund. The firm has focused on restructuring, capitalization and repositioning since its establishment in 2017. Its last big deal was the $28-million takeover of Pengrowth Energy, a one-time $4-billion company, in late 2019. Pengrowth had suffered as Canadian oil prices languished and it lost access to capital.

Waterous Energy Fund is now seeking targets in the United States as the oil sector south of the border contracts under declining cash flows and mountains of debt.

Even before the pandemic, the U.S. oil “tech-wreck” had showed itself over the past five years as producers and investors plowed piles of capital into drilling and hydraulic fracturing in regions such as the Bakken in North Dakota and the Permian in Texas. Returns have dwindled, Mr. Waterous says. U.S. oil output is on track to decline from 12.7 million barrels a day at the start of this year, to 9 million or 10 million a day by the end of 2021, and that will mean corporate casualties, he predicts.

“We think the North American energy industry is going to create a lot of special situations. We are a deep-value special situations investor,” Mr. Waterous says. “A large portion of the North American oil business over the next several years is going to be recapitalized, restructured and repositioned. For the U.S. oil business, this is going to be, ‘Honey, I shrunk the industry.’”

The deal flow in the oil patch has not been brisk during the crisis, but private equity is expected to play a role in consolidating the many small players in the industry that have struggled.

Calgary-based ARC Financial Corp. has invested more than $6-billion in energy companies over the past three decades. In one deal that could be a sign of things to come, ARC-backed Longshore Resources Ltd.‘s said early this month it was acquiring three small producers: Rifle Shot Oil Corp., Primavera Resources Corp. and Steelhead Petroleum Ltd.

As economies recover from the pandemic, some sectors will undoubtedly fare better than others. Looking ahead, a recent Preqin survey of institutional investors that back private equity – pension plans, insurance companies and foundations – found there is strong demand for specialized funds that invest in health care and technology, but less interest in funds that focus on sectors such as real estate and retailing, which have more troubled prospects.

“While our survey results clearly indicate a strong sense of caution among the investment community right now, there is much to suggest that investors are planning for the longer term and continuing to invest – in different sectors, in some cases,” Preqin analyst Ashish Chauhan said.

Even though dealmaking is nearly at a standstill and fund managers are sitting on more dry powder than ever before, more money is pouring into private equity. A Preqin study in April showed there are 3,620 funds out raising capital, and they are aiming to raise US$933-billion.

If private equity fund managers indeed add almost a trillion dollars to their coffers, the summertime pressure to do deals will only grow.

Courtesy of The Globe and Mail.

Authors: Andrew Willis, Mark Rendell, Jeffrey Jones and David Milstead.

With files from Sean Silcoff